Manuel Arguilla’s “A Story for These Times”

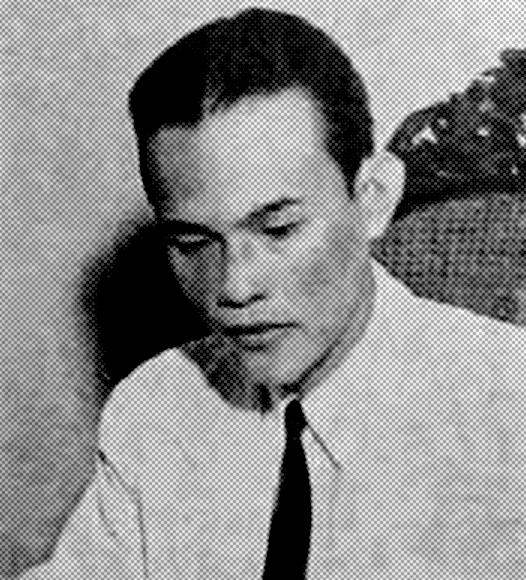

Many Filipino students know Manuel E. Arguilla as as an Ilocano writer of short stories in English. His works, such as “How My Brother Leon Brought Home a Wife” and “Midsummer,” have been read in high school textbooks for decades.

His portrayal of the rustic life of the early 20th century Philippines was endearing to the readers, having been published in literary magazines of his time. From these he produced his only book, a collection of 19 stories, in 1940.

Then came the Japanese occupation of the Philippines December 1941. Arguilla still managed to write during this time until he was executed in August 1944 by the Japanese.

Ironically a mere two years ago, Arguilla was present at a symposium of Japanese and Filipino scholars on 11 September 1942 at the Manila Hotel to discuss the strengthening of the cultural movement of the so-called New Philippines, with Claro M. Recto and Eulogio Rodriguez also participating. But his “collaboration” with the enemy forces was a facade because he was secretly organizing a guerilla intelligence unit.

The short story “A Story for These Times” was written for an issue of the Shin Seiki propaganda magazine in November 1942. This was one of his final works, the last one being “Rendezvous at Banzai Bridge” published in April 1943 in the Philippine Review.

I chanced to see a copy of this while looking through the scanned magazines of the Filipinas Heritage Library available online. “A Story for These Times” is about a town judge who chooses to become a collaborator to save his family and the townspeople.

It could be Arguilla’s way of attenuating the public’s fear during wartime conditions. To a careful reader, the story was by no means a complete subjugation to the occupiers.

Here is a copy of the story.